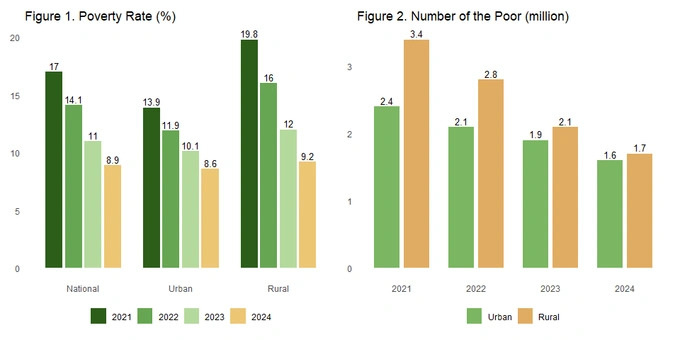

Uzbekistan has made remarkable strides in reducing poverty over the past four years. According to the latest Household Budget Survey (HBS) by the National Statistics Committee, the poverty rate has dropped from 17% in 2021 to just 8.9% in 2024 (Figure 1). This indicates that the share of the population living below the national poverty line has nearly halved during this period.

Much of this progress has come from rural areas. In 2021, nearly one in five rural residents were poor. By 2024, that figure had dropped to 9.2% — a dramatic decline. In comparison, the poverty rate in urban areas fell more slowly, from 13.9% to 8.6%. Around 1.7 million people in rural areas escaped out of poverty since 2021, compared to 0.8 million people in urban centers (Figure 2). As a result, the gap between rural and urban poverty rates has nearly closed, shrinking from 5.9 percentage points to just 0.7 points. Given that the incidence of poverty is now similar in both rural and urban areas, tackling poverty in the urban areas, where poverty has been declining at a slower pace, requires just as much attention.

Where are the poor located?

The poverty rate is not uniform across the nation — there are substantial disparities in poverty across regions (Figure 3). The latest figures show that Khorezm, Jizzakh, Syrdarya and the Republic of Karakalpakstan continue to struggle with poverty rates well above the national average. Meanwhile, Navoi, Tashkent City and Samarkand have managed to keep rates significantly lower.

But it’s not just about the level of the poverty rate. When we look at the absolute number of people living in poverty, a different story emerges. The largest numbers of poor residents are found in Fergana (350,000 people), Kashkadarya (341,000), Andijan (323,000) and Samarkand (317,000). These are populous regions where even a moderate poverty rate translates into a very high number of affected households.

There is good news too. Over the past 3 years, Samarkand, Syrdarya, Tashkent region and Karakalpakstan successfully reduced poverty by more than 10 percentage points. These improvements demonstrate that progress is possible, though uneven. Understanding where the poor live and how their numbers shift over time is essential for effective policy decisions.

The recent poverty reduction is accompanied by a rise in inequality

From 2022 to 2023, income growth in Uzbekistan was more favorable to wealthier households. In both urban and rural areas, richer households experienced faster income growth, while the poor saw moderate growth. Nationally, the top 20% of the population enjoyed an annual income growth of 33%, compared to 11% for the bottom 20% (Figure 4). This pro-rich growth widened the income gap between the rich and poor, raising the Gini coefficient (a key measure of inequality) from 31.2 in 2022 to 34.5 in 2023.

This increase in inequality also slowed poverty reduction. Our estimates suggest that poverty could have fallen by an additional 2.4 percentage points if inequality had remained stable during this period.

Yet 2024 brought a different picture. Between 2023 and 2024, overall, income growth decelerated but became more evenly distributed. In fact, the poorest 20%, especially in rural areas, saw stronger gains than other income groups. Rural households in the bottom 20% experienced a 19% income growth, nearly double the national average. This shift toward more inclusive growth helped accelerate poverty reduction in rural parts of the country, indicating that the distribution of income growth between the poor and rich can be as significant as the rate of income growth.

What factors contributed to poverty reduction?

Uzbekistan’s progress in poverty reduction hasn’t happened by accident. At the heart of this success lies one key engine: income from work. Labor earnings — in all their forms — have played the biggest role in lifting families out of poverty.

But the story is not the same every year. Between 2022 and 2023, wage growth was the main force behind poverty reduction, accounting for a drop of 1.6 percentage points in the poverty rate (Figure 5). Growth in remittance and social protection benefit also contributed to poverty reduction.

However, the dynamics shifted in the following year. From 2023 to 2024, the largest contributors were growth in business income, followed by wage and agriculture incomes. This growth of labor income accounted for more than 90% of poverty reduction during this period. Our estimates suggest that without social benefits, poverty in 2024 would have been 9.5% instead of 8.9%.

Interestingly, not all income sources contributed. Remittances and other forms of income had neutral or even negative effects on poverty reduction in 2024, likely reflecting shifting labor migration patterns or weaker support networks abroad.

The decline was notable among the poorest 20% of households, where the share of families receiving remittances dropped from 42% in 2023 to just 29% in 2024 (Figure 6). In contrast, receipt rates remained relatively stable across the rest of the income distribution.

Who is considered poor?

Let’s start with how poverty is actually measured. Each year, the National Statistics Committee surveys around 16,000 households across the country. The survey captures a wide range of data, from income (formal and informal) to employment, education, health, consumption and access to social support. Using this information, the National Statistics Committee calculates household income per person.

If that income falls below minimum consumption expenditures that is used as a national poverty line (669 thousand for 2025), the household is considered poor. Based on this method, Uzbekistan’s poverty rate stood at 8.9% in 2024.

What about finding poor families?

Identifying the families most in need is where things get complicated. Ideally, we could simply look at tax records, calculate each family’s total income, divide it by the number of household members and compare it to the national poverty line. In theory, this would allow us to identify the poor with precision. But in reality, it’s not that simple. This approach only works in an economy where most people are formally employed and fully participating in the government systems.

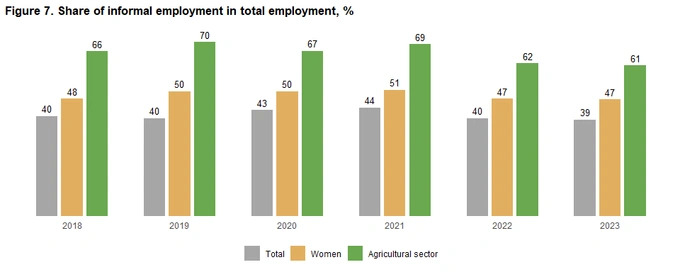

In Uzbekistan, however, informal employment remains widespread — nearly 40% of the workforce was informally employed in 2023. The rates are even higher for women, at 47%, and in the agricultural sector, where informal employment reaches 61%. These gaps make it extremely difficult to rely solely on administrative tax data to identify who truly needs support, particularly since the poor are the ones who are more likely to rely on informal employment.

In this context, alternative approaches are needed to identify the poorest households — especially when informal income is hard to measure. One solution is to rely on proxy indicators like asset ownership. For instance, families that own multiple homes, newer vehicles or land ownership could be reasonably considered better off. Authorities can set clear thresholds — such as excluding households with more than one residence or with multiple recent-model cars. For land, the government can estimate potential income per area and factor it into eligibility decisions. These are objective, verifiable indicators drawn from administrative data, and they offer a valuable layer of transparency and fairness.

Yet even these measures have limits. Assets can be hidden or registered under a relative’s name. Families may appear poor on paper while enjoying real, but undocumented, wealth. That’s why no single method can guarantee flawless identification of the poor. Instead, the targeting system must evolve continuously — adapting to new realities, tightening loopholes and staying one step ahead of the incentives to misrepresent one’s situation.

In Uzbekistan, that task falls to the National Agency for Social Protection, which operates registries through which the state identifies poor families and delivers child benefits, material assistance, disability and caregiver allowances, energy compensation and more.

One of the largest and most poverty-targeted programs is child benefits. Ongoing efforts have been made to enhance the program’s targeting methodologies. In 2024, post-checks and opinion of “mahalla seven” (mahalla officials) were introduced to refine the targeting approach. As a result, the overall coverage for this benefit was nearly halved from 15.7 to 8.3% reaching more than 1.2 million families (Table 1). These adjustments led to a slight improvement in accuracy of targeting the poor. The share of program beneficiaries who were in the poorest 20% of the population increased from 31.4% in 2023 to 34% in 2024, while the share in the richest 40% fell from 20.9% to 18.5% (Table 2).

In short, reducing the number of beneficiaries and spending did not automatically lead to better targeting of poor families in social benefits. There is still room for improvement in ensuring that social benefits reach those most in need. Further efforts to improve targeting methodologies and integration of registries could enhance the effectiveness of social transfers in poverty reduction moving forward.

In November 2024, Uzbekistan launched a new phase in its fight against poverty — the From Poverty to Prosperity program. This ambitious program puts communities at the center of the solution, aiming to expand social services, build a comprehensive registry of poor families and create 5.2 million employment opportunities. Families included in the registry for poor families are now receiving child benefits as well as necessary social assistance and services. By the end of the year, the registry for poor families and the existing single registry for social protection are scheduled to be fully integrated to deliver comprehensive social services. With these efforts, the government aims to reduce the national poverty rate to 6% by the end of 2025. Reducing poverty is not an easy task, lifting last cohorts out of poverty is even more difficult endeavor that requires better coordination.